What Makes Clocks by Coldplay Tick?

A peek beneath the surface of an alt-rock classic.

Clocks. I still remember where I was, an early morning in the car on the way to high school, when Clocks started playing, and I was instantly transported into another world. A hypnotic piano part, a cyclical yet interesting chord progression, the haunting vocal melodies—it all came together in a way that hit me deeply.

But what makes Clocks work so well? What’s happening in the music? Come along with me as we explore some of what’s happening behind the scenes in Clocks.

The Mixolydian Mode

The most interesting feature of Clocks, that immediately sets it apart, is its use of the mixolydian mode. Modes are essentially offsets of the major scale by a certain number of degrees; in this case five degrees. So even though Clocks emphasizes E♭ as the tonic, it technically uses the notes from the A♭ major scale (E♭ being the fifth degree).

What this means is, right out of the gate, Clocks has this hovering, never-fully resolving quality to it. In this mode, our ears want to hear an A♭ chord as the most resolved sound, because the notes being used all belong to A♭ major. But very interestingly, the A♭ chord is entirely avoided in the sections of Clocks that are in A♭ mixolydian, which purposely keeps us “hovering,” harmonically speaking, the whole time.

There are two considerations from this.

First, if you’re looking for more inspiration for your compositions, try writing in one of the modes. Each one is a totally different ballgame with unique melodies and chord progressions that only work in that mode. The dorian (2nd), lydian (4th), or mixolydian (5th) modes would be good places to start.

Second, consider withholding certain chords in your compositions for special effect. As we’ve seen in Clocks, by purposely withholding the A♭ chord, the hovering, unsettled harmonic atmosphere was heightened. You might do the same thing, withholding a chord such as the tonic to achieve a similar effect. Or, you might withhold a chord from some sections of your piece, and reserve its use for another, to add dramatic effect to that section.

Which leads us to another related observation.

Changing Keys Mid-Piece for Dramatic Effect

About two-thirds of the way through, Clocks takes an unexpected key change to D♭ major. Why does this happen here? I’d argue that, by this point of the song, they’ve developed the E♭ mixolydian atmosphere as far as they could, and our ears are just starting to get tired of it. By harmonically “switching gears” like this, they’re able to cleanse the listener’s harmonic palate, and keep them engaged.

Interestingly, they let this section “bottom out” on a D♭ chord, which in this context is the most resolved sound our ears want to hear, because the notes in this section all belong to D♭ major. This is in direct contrast with the rest of the piece, which purposely withholds the resolved chord sound, in order to perpetuate the hovering, unsettled, and cyclical quality of the chord progression.

This is an example of tension and release on a large scale. They create tension in most of the song by withholding a resolved sound, and they release that tension by delivering a resolved sound later in the piece, albeit in a different context than we expected. Which is part of what makes it so engaging.

Another question is, “why does this key change work so well?” Two reasons come to mind:

The root scales of the sections are closely related. If you know your circle of fifths, you’ll know that the notes from A♭ major (same as E♭ mixolydian) and D♭ major are only one degree apart, which means that only one single note changes between them (in this case G to G♭). What this means is, while the moment of the key change is somewhat jarring and unexpected, the ear quickly accepts it because so many of the notes are still in common with what just preceded it.

The key change was entered by stepwise motion. Immediately before, we were sitting on the ii chord of E♭ mixolydian, to be specific, F minor over an A♭ in the bass. At the transition, we’re given a G♭ chord first, which is only a step away for the bass to make. This helps make it more accessible to our ears. They could’ve chosen another chord from the new key, but they picked one that was only a step away, to make the transition smoother.

What does this mean for your music? If you have exhausted other means of developing your piece, if it calls for it, you might consider bringing in “the big guns” and doing a key change. And what helps make a key change work for the listener is getting into it smoothly, both by stepwise motion, and if possible by not too drastic of a harmonic change.

Linear Development

Part of what keeps Clocks moving forward, and not getting stuck in a rut, is that various elements in the piece undergo a subtle transformation and development over time. This is important, because a piece with such a cyclical nature like Clocks would probably gravitate towards getting stuck in a rut. But there is a healthy dose of change and development that keeps Clocks moving forward.

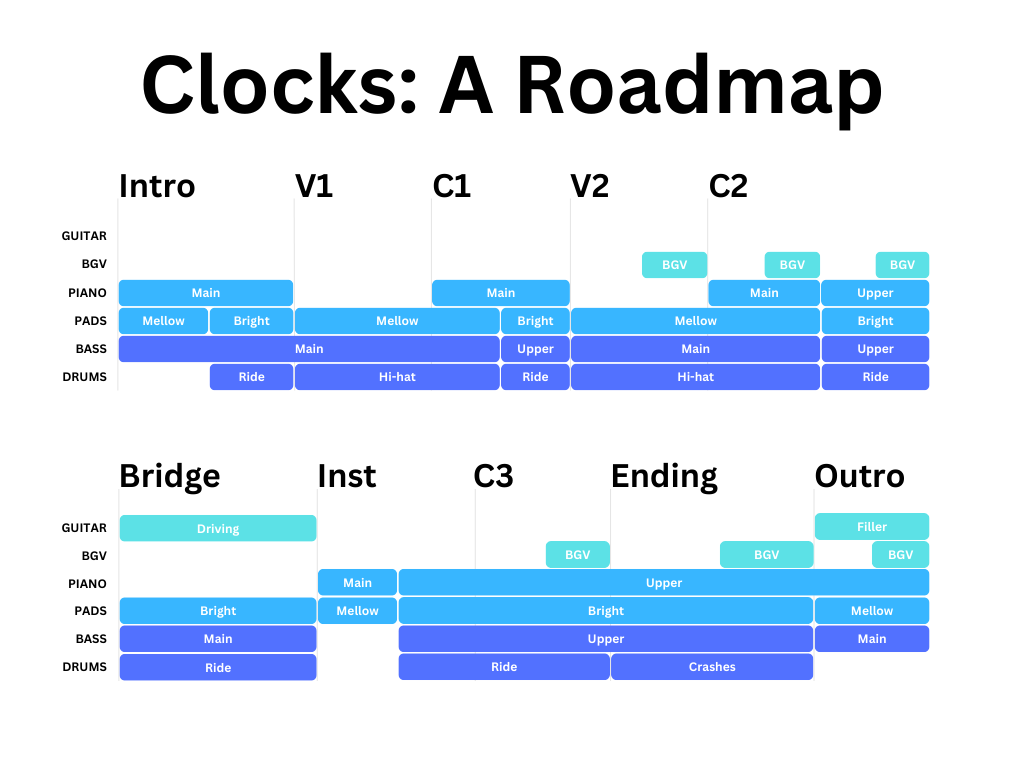

Here are some brief observations on a per-instrument level, roughly from the bottom of the frequency spectrum moving upward:

Drums: the use of cymbals is reserved for sections when things need a little push. And the use of crashes is reserved exclusively for the end, to help drive things home.

Bass: the use of a higher-register, slightly more interesting and melodic bass line is used in the same sections the drummer uses the ride cymbal, to drive things forward and provide a nice contrast to the ear. The only instance where this doesn’t happen is at the beginning of the song, presumably because you want to lay the foundation first before developing on it.

Soft pads: after laying the foundation in verse 1, near the end of verse 2, the otherwise basic pad part subtly climbs up in register to build tension.

Bright pads: the use of bright pads is restricted to those same sections where the bass’s upper register and cymbals are used, to further open up the high end of the frequency spectrum.

Vocal harmony: to add forward development and interest in verse 2, background harmony is added at the halfway point. It is used in a similar way in the chorus which follows it.

Piano: once the practical limit of development in the background harmony has been reached, it’s time for the piano to undergo an upward transformation just before the bridge. It’s important to note that this development has been withheld until other means of development have been exhausted first. If this piano part had changed earlier in the piece, Clocks likely would’ve run out of steam earlier.

Guitar: perhaps for a slight shift of overall timbre, the guitar does not feature prominently in the mix until the bridge.

So what’s the takeaway from all this?

By carefully controlling the pacing of how and when things unfold over the course of the track, Coldplay are able to craft an engaging arrangement with a somewhat limited palette of instruments. You don’t need a ton of instruments to make a good piece; you just need to thoughtfully manage whatever instruments you have there.

Conclusion

What’s fascinating to me about Coldplay’s earlier material, is that they’re able to create interesting and engaging pieces without the need for extensive music production techniques. By being aware of some music theory and carefully managing the resources they have, they’re able to create music that translates.

For us, as composers and producers, sometimes the answer is not to do more, but to do less, and do it well.